Find the accompanying Raven Bond podcast here!

Released: October 1962

Produced by Harry Saltzmann and Albert R. Broccoli

Directed by Terence Young

Plot

M16 spy James Bond is tasked with finding out what happened to Strangways, a British agent missing in Jamaica. Strangways was investigating Chinese scientist Dr No, in partnership with a CIA mission to see if radio disturbances coming from the region are purposely interfering with NASA’s moonshot attempts. Bond finds himself at Dr No’s secret island base and learns the truth behind the metal-handed Doctor’s plans.

Famous For:

Being the first Bond movie.

Smokin’ hot Sean Connery.

Launching the concept of a Bond villain.

Ursula Andress in THAT BIKINI.

There’s a moment about three-quarters into Dr No when it definitively turns from a spy movie into a Bond movie.

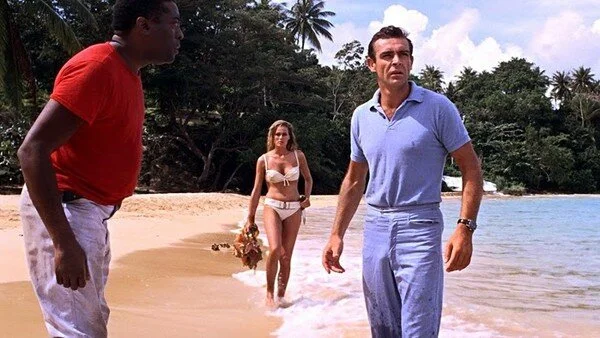

The first instalment of a now 58-year-old film franchise has flickers of it before then, of course: the gunbarrel opening shot; the theme song and stylised opening title sequence; Sean Connery tying himself forever to the role with Bond’s immortal self-introduction at a London casino; Bond’s sparring with M and Miss Moneypenny; Ursula Andress stepping out of the water and into wet dreams in that white belted bikini. But Bond’s investigations in Kingston, the escapes from various attempts on his life, even the controversial cold-blooded murder of the traitorous Professor Dent, read much more like a spy procedural than what we now know in our bones as a “Bond movie”.

The moment Dr No - and in a sense, spy movies as a genre - shifts tectonically is when Bond and Honey Ryder, captured on Crab Key, post-decontamination and drugging, are shuffled into the eponymous villain’s dining room. They are drawn to a huge glass panel through which they can see dozens of oversized fish.

“One million dollars,” intones the eponymous villain, a menacing musical sting underscoring his dramatic arrival onscreen. “You were wondering what it cost,” Dr No continues, before introducing himself, explaining the aquarium’s dimensions and bestowing drinks upon Bond and Ryder.

It is this moment that coalesces so much of what would make the fantasy of Bond: the villainry.

In this scene, and in the dinner that follows, the Bond villain gets an almost pitch perfect template in a matter of minutes. Egotistical yet intelligent, often with a physical flaw representing their hubris (Dr No’s metal arms are a result of his experiments with radioactive elements); carrying out schemes from an over the top secret lair staffed with loyal henchmen; and bestowing a refined and cordial welcome to Bond - including a handy revelation of plans - despite ticking all boxes on the Psychopath Checklist.

Now this is not to disparage the character of James Bond in any way, nor in Sean Connery’s portrayal. He oozes Bond from the very start, despite his baby blue island ensemble and some incredibly high-waisted pants.

That’s 12 inches if I’ve ever seen it.

Bond is enough of an enigma that you can project your fantasy self onto him, and hooooooo boy do I project my fantasy self right on top of 1962 Sean Connery’s face.

But Bond’s enemies are elevated to the fantastical, ergo Bond himself is elevated. Which came first, the super spy or the super villain? Is the spy super because he kills the super villains? Or are the villains super because they can only be killed by Bond?

1997’s super parody Austin Powers played with this sense of the fantastical brilliantly; despite aping Blofeld’s shaved head and facial scarring (of the Donald Pleasance variety), I argue there is more of Doctor No in Doctor Evil:

And while Dr No explains his background with a few simple sentences...

“A handicap is what you make of it. I was the unwanted child of a German missionary and a Chinese girl of good family. Yet I became treasurer of the most powerful criminal society in China.”

...Mike Myers extended this premise into the equally-as-classic Dr Evil monologue.

The refined dinner sequence also gives us the concept of SPECTRE, the Special Executive for Counter-intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge and Extortion. SPECTRE remains a brilliant invention of Ian Fleming - a device that allows the stories to move beyond the East/West Cold War dynamic, and bring in a bombastic, apolitical, uber-scheming Big Bad that could allow the development of increasingly fantastic villains with increasingly distinctive henchmen and increasingly incredulous plans for world domination.

It also allows Bond to be positioned in the moral right; there is no way The Pride of Her Majesty’s Secret Service could be tempted by Dr No’s offer to join his morally bankrupt group of (admittedly ambitious) petty crooks. An even deeper analysis might suggest Bond cemented a certain notion of British-ness in that stance; something that is arguably still having effects to this day.

One of the reasons I was so disappointed in 2015’s Spectre was that I was SO VERY EXCITED to have the organisation back. What better name for a Bond film than “Spectre”? But then the film seemed to undermine the whole point of SPECTRE. But I’ll hold back from starting a rant on that - we have many years of films before we get to my MANY THOUGHTS on Spectre.

Safe to say Dr No dangles SPECTRE in front of viewers in a most delicious way - enough that the film wraps up satisfyingly with the death of Dr No while hinting that James Bond’s meddlin’ hasn’t quite stopped SPECTRE getting away with it.

Trying to make a joke work on two levels.

Bond films are of course action movies, and Dr No serves up Bond in true blunt instrument fashion in his stymieing of Spectre’s plans to scupper NASA’s space launch - which, by the way, sets a precedent in having nods to real-world current events in the Bond films (the other being the Goya’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington, missing at the time of the film’s release, turning up in Dr No’s lair).

In hilarious contrast to Dr No’s one million dollars for a single aquarium, production designer Ken Adam had about £15,000 to construct the Crab Key facility to be blown up for the film’s final showdown. The main control centre has a clinically believable nuclear reactor pool which consumes Dr No after his final showdown with Bond - his metal arms putting the iron in irony as he is unable to pull himself out of the water.

Bond rescues Honey Ryder from an overly complicated death by drowning, and the pair commandeer a small tender as the whole operation is blown up in miniature, a tiny yet mighty celluloid cataclysm.

The CIA, led by Felix Leiter - Jack Lord’s only appearance as Bond’s US counterpart because he wanted too much money to return - rescues the pair once their craft runs out of fuel, but Bond lets the tow rope slip in order to spend more time macking on with Honey Ryder.

Sure, she’s only known him for a day, but he did take a protective role towards her on Crab Key, and besides, James Bond has a magic penis, and we will see more evidence of this in the coming films.

Speaking of “The Girl”, a key reason for this rewatch and re-examination of the Bond oeuvre is to develop a long-held view of mine - that the Bond Girls (or “Bond Women” as they are now being rebadged; I take no offence at “Girl” so will use the two interchangeably) are more often that not key drivers in the story with a degree of power and agency often discarded by critics.

The Bond character is easily denigrated as misogynistic - even self-referentially in one of my enduring favourites, 1995’s Goldeneye.

And look, the franchise’s hands aren’t clean. I’m not expecting to change minds here; given I’ve never formally studied gender theory or even film theory, I may find myself without a (shapely) leg to stand on.

But I grew up watching these films, and I consider myself a feminist. I hate a lot of the ways women are portrayed in media, but I find the role of women - their brains and their bodies - in the Bond canon as really bloody fascinating. So here are my thoughts on Honey Ryder as a force of nature, and how she represents a primal passion Bond possesses but must contain.

We meet Honey Ryder, of course, as she rises like Venus or a mermaid or siren or whatever mythical creature you prefer out of the aquamarine water of the Caribbean.

Ryder’s bikini may be soft white, but the knife she carries on her belt is sharp steel: in reaching for it when Bond approaches, she represents a sort of “experienced innocence”.

“What are you doing here? Looking for shells?” she asks. “No,” Bond answers. “I’m just looking.”

As are we all, James. Andress’ voice may have been dubbed for clarity (her native Swiss accent too thick, apparently), but her body and her presence is all her own. Honey is cautious about this new element in her world, but also intrigued. She tells Bond her name, and asks for his in return. For his part, Bond attempts to sidle into her world of diving for shells and island-hopping by simply introducing himself as “James”. No fancy Bond, James Bond will do here.

After Ryder, Bond and Quarrel (whose incredulous stare upon seeing how Bond has somehow discovered a literal water goddess in their brief separation is a scene-stealer) are shot at by Dr No’s goons, Bond wants to get Honey out of danger and away from the island. Fortunately for Bond and Quarrel, her boat is shot up, which allows her to show them a way to escape, sticking to a creek to avoid the dogs’ getting their scent. Resourceful, she shows Bond how to get the mosquitos off him by rubbing him with water.

Later while resting before nightfall, Ryder tells Bond how she believes her father was killed on Crab Key. He had been a marine zoologist who took his daughter to the Philippines, Bali, Hawaii “anywhere there were shells”, but failed to return to Kingston after diving off the island.

She tells Bond of being raped by their landlord after her father disappeared. Bond receives this information with little emotion; it’s telling that he reacts far more strongly to her admission that she put a female black widow spider in her rapist’s mosquito net while he slept and it took the man a week to die. Her formal education may have simply been reading Encyclopedia Britannicas, but her informal education travelling the world has equipped her with plenty of important information.

Bond’s stunned silence is enough to prompt Ryder into asking “Did I do wrong?”. Bond’s response is not anger, but stern reproach - having recently fallen prey to a spider in his bed, you could argue he might be a bit sensitive on the subject. “I wouldn’t make a habit of it,” he warns her.

007 is licensed to kill; he does so methodically and under the auspices of Her Majesty’s Government. Bond is the concrete construction that can tame wild ground; Ryder is the grass and weed and root that finds its way through to the light. Bond is not threatened by Ryder per se, but he cannot let the notion of what he does as just and “civilised” killing be contaminated by Ryder’s natural compulsion for justice. Because then he might let a crack of doubt in. For example, Bond didn’t NEED to kill Professor Dent.

He could have just as easily taken him into custody as he did Miss Taro. But there was some element of revenge there: for facilitating Strangways’ death; for betraying Britain; for lying to Bond; for trying to kill Bond; whatever. Bond could never admit that of course; certainly not like Ryder’s candid admission of murdering her rapist.

Ultimately Ryder cannot play a role in defeating Dr No because he is a man of science and has to be destroyed clinically; also because it’s a Bond movie, it’s 1962 and it’s still a studio system, a literary convention and a societal requirement that strong, clear-thinking men win battles and save/get the girls.

Is positioning “man as logic” and “woman as emotion” too cliched for a first essay? Quite possibly. Later films let cracks form in Bond, colouring his moral certainty. Let’s see if I can get more sophisticated as the filmmakers’ play with the notion of Bond’s identity.

As we will see through the Bond franchise, particularly the earlier films, there are a number of uncomfortable and cringe-worthy moments in terms of casting. In this case - the actor Zena Marshall may have had “exotic” looks, but a black wig and heavily winged eyeliner does not an Asian woman make. Thankfully her character Miss Taro speaks with a British accent, so at least there is no “yellow voice”.

Joseph Wiseman too is given a slight makeover to give his Canadian features a more Oriental look for Dr No’s mixed race heritage - but at least Bond’s disgust at him has more to do with his character and evil intentions than his race.

No doubt many people with disabilities detest the physical “flaws” given to Bond villains. This will be a recurring motif I’m interested to return to in each film. Certainly all the Bond villains have intense personality disorders - perhaps these days it is easier to convey this without the cinematic shorthand of a literal “flaw”. As it is, I still find Dr No’s metal hands a memorable piece of design that helped secure the idea of the Bond Villain.

To finish off, an observation that hit me for the first time on this rewatch of the film, and caused me to chuckle.

One of my favourite characters in this film is Quarrel (John Kitzmiller), the Cayman Islander fisherman who works with both Felix Leiter and Bond to solve the mystery of Crab Key. He is seen wearing a red shirt throughout the film, and indeed his character is one of many offsiders, allies and fellow agents who will be sacrificed while helping James Bond.

This film was released four years before the original Star Trek TV series, and its notorious “red shirts” - dispensable members of the Enterprise. Did Gene Roddenberry take some subconscious cues from Bond?

Thanks for reading this first instalment in my James Bond retrospective. Don’t forget to check out the accompanying Raven Bond podcast!

James Bond will return in From Russia With Love. Until then, please enjoy this GIF of James Bond’s superlative driving on rotoscope.